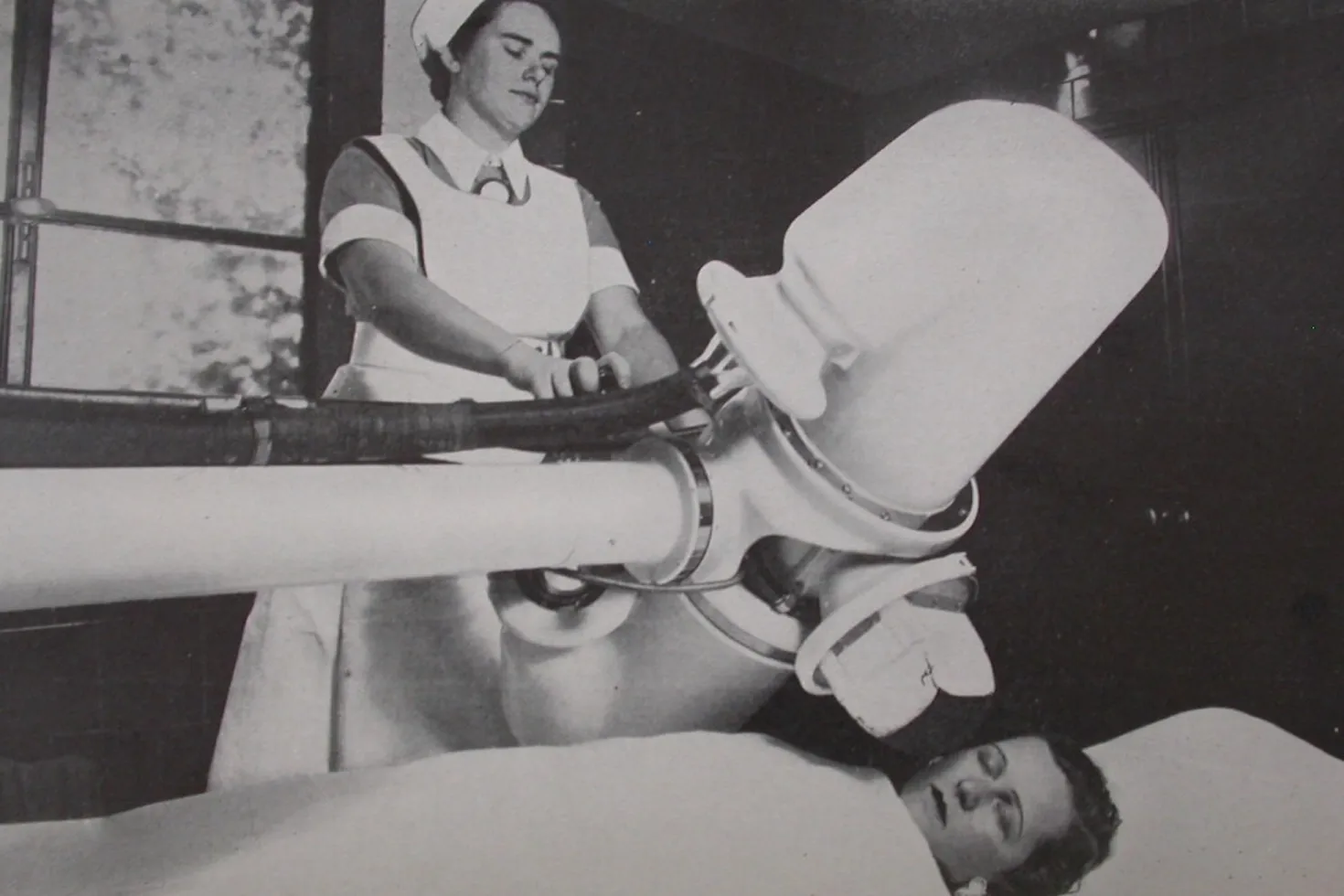

Healthcare worker performing a mammography, 1948.

Attempts to cure cancer have spanned centuries and been influenced by culture, region and religion, and those working to understand and treat cancer have faced similar problems throughout history.

Thanks to modern medicine, we are constantly seeing better survival rates. Yet still today, cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide. Looking at the past can provide valuable lessons in understanding cancer and managing innovation.

In this episode, Cary Adams, CEO of UICC, speaks with Professor Yolanda Eraso, from London Metropolitan University, and Professor Carsten Timmermann, from the University of Manchester.

See podcast transcript below

Listen on: Spotify | Stitcher | Apple Podcasts | Amazon Music | Audible | Deezer

Get notified of new podcasts by email

Podcast transcript

Cary Adams: Welcome to Let's Talk Cancer. I'm Cary Adams, the CEO of the Union for International Cancer Control. Attempts to cure cancer have spanned centuries and been influenced by culture, region and religion. From magic spells in ancient Egypt to the use of bore teeth and tinted led during the Greek era and treatment by starvation or by cold in 18th century England. Thanks to modern medicine such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, immunotherapy and genomic testing, we are constantly seeing better survival rates. Yet cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide, and those working to understand and treat cancer have faced similar problems throughout history. Resource allocation. Disparities in care. Religious and cultural barriers. Medical scepticism, to name but a few. Looking at the past can provide some valuable lessons and help us perhaps better understand how cancer impacts the world today and what risks it poses for tomorrow. To talk us through the history of cancer, from the earliest known descriptions of cancer in Ancient Egypt to the modern era of precision medicine is Professor Yolanda Eraso from the London Metropolitan University, who works in applied health research and has also studied the history of female cancers with a focus on Latin America. And our second guest is Carsten Timmerman, professor of history of science, technology and medicine at the University of Manchester. He has a special focus on modern European history and lung cancer. So welcome to you both and thank you very much for joining us for this podcast. Yes. Can I start with you, Yolanda? So when do you think in the past did we really see the first identification of a cancer? And what were some of the original attempts to treat the disease?

Yolanda Eraso: This is taking a very broad brush approach. So the first descriptions that we know of are from classical antiquity in the Greco-Roman world. The ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates, and his followers as well, observed and recorded the various tumours and growths and described apparently what is considered to be the first case of breast cancer in history. And he used the term karkinos, which means crab in Greek to describe tumours, he observed, likening it to a crab that adheres to its surroundings with its claws. So from there is that association with crab and karkinos, but also in the Greek or Roman times, the concept of humours play a significant role in the understanding of cancer. So Hippocrates believed that the body was composed of four fluids or humours, that is blood, phlegm, the yellow bile and the black bile. And when the humans were balanced, a person was considered to be healthy, both mentally and physically. But when there was an imbalance, this caused physical and mental disease. For example, yellow bile that was thought to be located in the liver will lead to anger, for example, and too much black bile, which they believe was from the gallbladder could lead to depression. The black bile was thought to be particularly bad and an excess in the body risk causing illnesses and also in particular cancer.

Yolanda Eraso: So just to sum it up, this. The standard idea through antiquity and right until the 17th century was that all tumours resulted from inflammatory processes caused by an abnormal flux of humours in particularly the black bile. And that would only change right in the 17th century as we have new developments on cancer and surgical practices with dissection and alongside autopsy and understanding of blood circulation, for example. There is obviously, we always say a bit of a caveat. Of course, in our understanding of what earlier periods might have understood about cancer and this always a risk of performing sort of retrospective diagnosis on their writing. So we should avoid that.

Carsten Timmerman: I think just to pick up from Yolanda, I mean, as she said, it's quite difficult to draw a continuous line through the history. We can either do what she's talked about, we can take descriptions, old texts and align them with what we understand to be cancer, but we can't be sure whether it was the same thing. It just sounds plausible. Or we can project backwards and and look at ancient remains and see whether we find signs of of cancer in the bones, for example, which we can't do. So there is really it's very difficult to say anything about the period before, say, 1800, when autopsies became routine, part of medical education, kind of hands on, frequently performed. And only then you also find regular descriptions of cancers that are not on the surface. Usually, the old descriptions often refer to breast cancer because it was ulcerating. You could see it from the surface while anything inside the body, the the symptoms are very diffuse and very easy to confuse with something else. So lung cancer, for example, you can't really reliably diagnose before you have autopsies.

Cary Adams: There are centuries and centuries, if not, you know, thousands of years of cancer being evident. But what is the story about defining moments of cancer treatment?

Carsten Timmerman: The key developments are the move to pathological anatomy as a key discipline around 1800, which comes with the systematic quest for lesions. You know, people look for lesions and that's what an ulcer or what a tumour is. It's a lesion that you can find in the autopsy and that then you can associate with certain symptoms. And at the same time, you get descriptions of tissues. So you get associations of these weird tissues, which may not be the same as normal tissues, and then we get to the next key step, the understanding of cancer as something which is characterised by cells dividing out of control. That's basically our understanding. The different understandings don't necessarily lead to different treatments. Very often you keep the same interventions that have been performed before. You just reinterpret them like surgery, cutting, cutting out the ulcer. Don't need cell theory to for that to make sense. The first modern intervention is the radical mastectomy, which is surgery. So it's an old style intervention, but it's conceptualised in terms of applied cell theory. You don't only cut off the tumour, you also follow the way in which cells travel and in which metastases develop. And then you get radiotherapy as the next intervention surgery. Of course we continue to do so. But then there are x-rays and radium. It comes not only with the new intervention, but also with new organisational ideas for radium is expensive, x ray equipment is expensive. So you get these collaborative networks, you get big, important cancer centres in Paris and Stockholm, in Manchester, and then really extensive referral networks and quite elaborate organisations around there. It's a step not only in terms of the actual intervention, but also in terms of the organisational context. And that kind of leads to the idea that maybe it's good to get organised even beyond national boundaries and organise this internationally.

Cary Adams: Yolanda, obviously you've specialised in women's cancer specifically. Breast cancer is sort of held up as one of those cancers where we've made dramatic improvements in survival rates over the last like 80 years or so with the ability of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgery, etcetera, etcetera. Can you describe what you thought were the key moments in that journey to get to a point where, you know, most women in a high income country, particularly caught early, can actually survive their cancer?

Yolanda Eraso: One aspect that was crucial in breast cancer and also for cervical cancer as well was early detection. I think that in the case of breast cancer and cervical cancer as well, there were both diagnostic tools that were introduced for early detection in South American countries, particularly Argentina and Brazil, Uruguay as well. One was called Buscapé for cervical cancer because it became the technique of preference for asymptomatic women. It came very early on to Argentina and Brazil. We are talking here 1928, 1930, and those gynaecologists were trained with Heintzelman, which is the person, the gynaecologist, who would develop the colposcope and started to be standard procedure in gynaecological clinics to identify that particular cancer of the cervix. But then it was taken back in Europe and the US after the 1950s. In the case of breast cancer, I think it was very important the contributions of radiologists from Uruguay. Raul Leborgne, who developed the mammography technique a bit as we know it today, which consisted of compression of the breast to ensure that the ray, the x-ray were directed to a focal point and not damaging all the healthy tissue. And so by the 1970s we have screening with mammography as a procedure for early detection of cancer.

Cary Adams: Which is fantastic. And it saves so many lives, doesn't it? So many lives. I had the great privilege of doing a podcast with Mary Gospodarowicz, who a past president of UIC, who has been leading the TNM staging classification for many, many years. And of course that that did come from Uicc in the 1950s. And we believe it's an important part of the armoury of addressing cancer around the world today because it gives a language of communication between oncologists on the type of cancer, the staging. Et cetera. Et cetera. Carson In your opinion, how important was that, that piece of collective work in terms of helping the community?

Carsten Timmerman: Absolutely crucial. The standardisation of the language by which you communicate results is absolutely crucial. That's I mean, that's the same for any other condition, but possibly even more so for cancer, because you look at a long-term development and that develops over a long period of time. And in order to know what others talk about, you need to agree on a fairly simple way standardising the language. It sounds trivial, but it's not trivial at all. And you couldn't do it without an international organisation, which people subscribe to. And I think the the context for this was quite crucial that it I mean, it really took off after the Second World War when people were keen to to talk to each other and to collaborate. And health is a field where you can do that even during the Cold War, even if you disagree about other fundamental things, nobody can disagree that it's a good idea to be able to exchange results on improvements in cancer treatment.

Cary Adams: And the the context of that is very important. I mean, forget there wasn't the podcast model there. There wasn't the sharing on social media. Even the academic journals were somewhat limited in terms of sharing. It's amazing that the people came together to address what clearly was a major challenge and perhaps we could talk about risk factors. I mean, we still struggle to get risk factor information across to people to understand the issues of, you know, smoking and alcohol use and poor diet and physical activity, obesity, etcetera, etcetera. But in your opinion, what were the key breakthroughs in terms of understanding risk factors and communicating them.

Carsten Timmerman: With the pre-modern approach to medicine? You'd assume that bad behaviour, sinful life, lack of sleep, too much sex, to little sex could push your constitution in a direction where it would turn into illness. What you get in the 19th century is the attempt to identify clear causes for clearly defined conditions. It's very difficult to establish clear causes, and they develop over a long period of time. But you can find some associations. And smoking, for cancer, is the standard story. The idea of the risk factor emerges again in the 1950s. People apply some more sophisticated epidemiological methods, which of course need things like staging and need standardization and need international exchange because you need large numbers, you need to compare, and then you need long term follow up. The first risk factor studies were done with people who had developed a form of cancer, say they had lung, they were lung cancer patients, they had a diagnosis of lung cancer. And then you would send people into the hospital with a questionnaire and they would ask them about usually their workplace. So would they be exposed to suspicious substances at the workplace, their residents. So are they somewhere where there are roads? Exhaust fumes were seen as one as one possible candidate or habits like smoking and smoking was suspicious. It was suspected to cause illness and especially lung cancer from really the early 20th century.

Carsten Timmerman: But the tools to establish that weren't available and the incidence wasn't really that threatening or wasn't seen to be that threatening because, you know, people weren't diagnosed with cancer. They were dying from a respiratory illness. But that respiratory illness may have been bronchitis or it may have been tuberculosis. And so cancer wasn't really suspected. And when people were more reliably diagnosed with cancer, you could ask them those questions. So the next step is cohort studies, prospective studies, and now it gets very expensive and difficult to organise. So now you what you want is a healthy population and you want this healthy population. You want to ask them in regular intervals once a year, ideally how they're doing. Are they still smoking? For example, if we're looking at smoking as a suspicious possible candidate, have they stopped smoking? What else are they doing? And then you at some point they die and you get or they get sick and you get a diagnosis and then you get if you have a large enough cohort, you can associate those things that you've asked them about every year with what their cause of death or the cause of their illness.

Cary Adams: I mean, the point that I take from that is the power of research and how important it is for us to do great research on the risk factors for cancer and all sorts of things. So, Yolanda, can you talk about the research, the world of research and how that has progressed over the last decades and how it's helped, particularly women's cancers?

Yolanda Eraso: There has been a lot of research on female cancers initially because these things have been so exposed, so easy to access them, so difficult to conceal as well. Cervical cancer produces, you know, a lot of symptoms and that was difficult to to hide. And also some smell as well when they became ulcerated. And in breast cancer as well because there was a point in which they can see those tumours, as I was describing, with this notion of the crab. So that visibility gave them much more research and focus and advance as well. Pre-cancer, you know, that notion of catching cancer early, at an early stage of development, and for that these two cancers have been really pioneering, if you like. I mean, in terms of after them, they started to apply the same notions to all cancers in other areas. There is also another area which is related to this, which is the issue of gender and culture and biology and how these interact at different points in time. We can see this through reproduction, for example, and how it had a greater biological relevance in women than in men, which sometimes led to two gender associations between sexual behaviour and cancer or disease and cancer as a female disease. Scientific knowledge in this sense has considered the uterus or the breast. When they degenerated they did not fulfil the function that is pregnancy or breastfeeding that had been working on hormonal treatment for breast cancer. I think it's a good illustration of gender and its influence. Back in the 1940s and until the 1970s. Testosterone therapy was used for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer and produced quite positive results in women.

Yolanda Eraso: And they found that it did have an impact in reducing or shrinking the tumour. It did have an impact, above all, in offering women well-being in terms of avoiding some side effects such as nausea or fatigue. However, male doctors in particular were concerned about the Masculinizing side effects of the drug, which included the growth of hair and the deepening of the voice. And so that was the only side effect that they were considering. What you see is that testosterone obviously stopped being used. However, when Tamoxifen, which is the drug that works as an anti-estrogen, when that drug was approved back in 1973, the findings emphasised the fact that Masculinizing effects were not observed. So that was the positive in comparing the two drugs. The positive of using tamoxifen as opposed to testosterone. But on the other hand, we know that currently the side effects of Tamoxifen and anti-estrogens in general are really a concern in terms of non-adherence to to these medications. It is estimated that around 50% of women do not adhere at year five of treatment. And the side effects of Tamoxifen include hot flashes, fatigue, joint pain, low libido, depression and so many other factors as well. But these factors were downplayed and disregarded at the time and continue to be problematic today. So in summary, we can say that gender notions and biological concepts of female cancer have been historically interacting, but not always. This interaction has meant and full progress in clinical practice and understanding.

Cary Adams: History is very important. The ICC is particularly conscious of that in our 90th anniversary. Carson What do you think? History important as we continue to fight cancer around the world?

Carsten Timmerman: I would say what history teaches us in this regard is to be realistic about your expectations. The usual pattern in the history of cancer treatment has been to apply something which worked for one cancer to all other cancers and then to find it doesn't actually work as well for other cancers. So radiotherapy is good for certain cancers, not that good for others. Chemotherapy or different chemical interventions. Equally, they work well for some conditions and not that well for others. For lung cancer, a lot of interventions haven't worked. So while this is a difficult lesson, I think that's to me the most valuable lesson from history.

Cary Adams: I think is a lesson to what my mum used to say to me. We try, try again. So we learn through error as we as we go through. But it's, I think United's perspective is we also feel that a lot of the knowledge we have today is not used well enough around the world. And, of course, if we did that tobacco control, which you were talking about earlier, if we just applied that look at the millions of lives we save globally. Yolanda, let me pass it to you then. History. How important is it in your world?

Yolanda Eraso: Knowledge about historical past can also influence the design of current interventions, make them more effective. With that, I'm considering multi-cancer early detection, which is a blood test where DNA is analysed for the detection of around or up to 50 types of different cancers and it could be soon available in clinical practice. So there's a lot of uncertainty of what benefit this type of screening may have in the population, what type of harms they might cause, the inequalities in health they might lead to. And the history of cancer screening and early diagnosis can provide insight into the type of studies and information that will be needed in order to understand and better prepare interventions, address in these type of challenges. For example, the issue of inequalities in cancer outcome. It is critical to know that the achievements in cancer control, such as screening and new treatments, have historically exacerbated disparities based on ethnic or socioeconomic groups and geographic differences as well. So therefore much work should be done in analysing the feasibility with these multi-cancer centers. Is it possible to reduce these inequalities that we see today? This also the need to explore the acceptability for certain population groups, that is, the screening behaviour and including stigma and fear of cancer, which there's a lot of history as well, studies analysing these issues in particular, and stigma and fear of cancer affect certain population groups more than others. And so all these factors have been explored through the history of of cancer. And I think they are very relevant in terms of lessons, in terms of issues that might affect the implementation of a technique that could be very successful. It could be a breakthrough indeed. But there is a lot of social psychological aspects as well that needs to be looked at or information is needed before implementing this into the large population as a screening method.

Cary Adams: And that's super. Yolanda Carlson. Thank you very much for your time. It's been very interesting. I've learnt a lot. Clearly, as a as a CEO of Uicc, I am fully acknowledging the fact that people before me over the many, many decades that UHC has been together have made great advances in our understanding of cancer and the treatment of cancer. And I also like to thank you personally, both of you, for your history in being involved in this particular area and the commitment you show to cancer control. So thank you very much and I wish you a good day.

Carsten Timmerman: Thank you so much. Thank you.

Cary Adams: Thank you for listening to Let's Talk Cancer. We hope you enjoyed the episode. If you have a moment, please do give us a rating and share the podcast. It really helps us reach a wider audience and inform more people about issues surrounding cancer. For questions and comments, please don't hesitate to contact us at communications@uicc.org. Before you go, I'd like to recommend another podcast, The Voices of the Health Revolution Podcast, produced by the NCD Alliance, which shines a light on the trailblazers leading bold action on non-communicable diseases, including cancer, even when that means taking a stand against the big industries. Find voices of the Health revolution at ncdalliance.org.

Last update

Thursday 31 August 2023