The antibody-drug conjugates targeting cancer cells with increased accuracy

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are revolutionising cancer treatment by targeting tumours more precisely and reducing side effects, offering new hope for patients with various types of cancer, including those in advanced stages.

Cancer is one of the most challenging health crises of our time, with one in four people worldwide expected to develop the disease within their lifetime. For the past several decades, chemotherapy, surgical procedures and radiotherapy were the most advanced tools available for physicians to treat tumours. In more recent years, new approaches have been introduced that are giving physicians new options, including immunotherapies, which stimulate the body's own immune system to help kill cancer cells and other more targeted approaches.

An example of targeted therapy is antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which are designed to deliver a cancer-killing drug directly to tumours, while reducing some of the side effects often seen with traditional treatments. Today, scientists are working to unlock the full potential of ADCs to improve outcomes for patients across many different cancer types.

ADCs may be about to change the landscape of cancer treatments, says Scott Peterson, director of ADC discovery and cancer immunology at Pfizer. ADCs are a group of targeted cancer drugs made from a combination of monoclonal antibodies, which help to target the treatment towards cancerous cells, and a cytotoxic drug, which kills those cells. ADCs bring the cancer cell-killing drug closer to the intended target. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy, by contrast, are not targeted, which means that some of the cytotoxic drug finds its way to non-cancerous cells – causing damage to healthy tissues.

Having the option to more specifically target treatments to cancer cells is a very exciting development, says Peterson. The first ADC was developed by Pfizer and approved by the FDA in 2000 – the emergence of monoclonal antibodies for use in ADCs has propelled cancer research forward. The number of ADCs developed by a range of companies and approved for patient use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is now in the teens for numerous types of cancers, including bladder cancer, cervical cancer, leukaemia, lymphoma and breast cancer.

Today, there are more than 100 new ADCs in clinical trials, and more are expected to be approved in the near future. The hope, says Peterson, is that the addition of more ADCs will provide patients with a broader range of treatment options, allowing for more targeted and effective care.

How do ADCs target cancer cells?

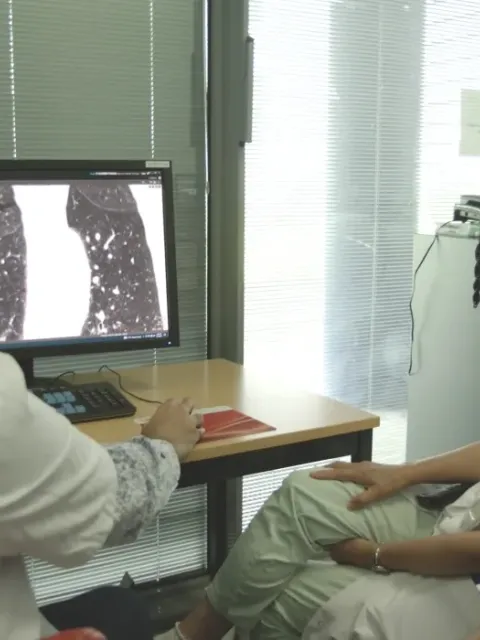

By designing ADCs to bind to specific proteins on the surface of tumour cells, the cytotoxin can be targeted more specifically to cancerous cells, resulting in those cells receiving a longer exposure to the drug, explains Sara Hurvitz, a doctor of medicine, head of the division of haematology and oncology at the University of Washington Department of Medicine and senior vice president of the Clinical Research Division at Fred Hutch Cancer Center, who researches targeted therapies for breast cancer. "[ADCs are a] Trojan horse technology where the monoclonal antibody detects and delivers the chemotherapy more specifically to cancer cells," she says.

"We've seen several ADCs now address a variety of different cancers," says Peterson.

Another breakthrough has been with ADCs in combination with other treatments, such as an immunotherapy that inhibits the PD1/PDL-1 pathway. PD-L1 is a protein highly expressed in many types of cancer that can block the ability of the immune system to treat tumours by binding to PD1 expressed on immune cells.

Researchers at Pfizer are evaluating the potential of combination treatments, including ADCs combined with PD1/PD-L1 inhibitors, to treat people diagnosed with certain advanced cancers. Subject to successful clinical development and regulatory approval, the hope is that these combinations could change the standard of care for certain tumour types.

"I think that we're going to continue to see ADCs combined with cancer immunotherapy, which [in combination] may have the potential to bring additional medicinal value to patients," says Peterson. "It's going to be critical to continue to design ADCs to work in combination with the patient's immune system."

Although cancer researchers are making headways in the development of ADCs, they are still facing problems.

"ADCs represent an innovative technology," Peterson says, "but they are not perfect." Currently, there are still side effects that can be challenging for patients, he adds. There is the potential to improve and refine the three parts of ADCs – monoclonal antibody, linker and cell-killing drug – for better safety and efficacy profile. By finding other mechanisms of action – or ways that drugs produce an effect in the body – researchers may be able to improve the way that ADCs discriminate between tumours and healthy tissues.

The better ADCs are at identifying tumours, the more effective they are expected to be at destroying tumours while limiting damage to healthy tissue. "What we all want to do is be effective at treating cancer while doing minimal harm to the patient," says Peterson.

One of the key areas Peterson would like to see development in is lung cancer. Currently, the five-year survival rate for patients with lung cancer in the US is 26.6%, and in the EU is on average 15% – although five-year survival rates vary quite widely, from 20% in Austria and Sweden to 8% in Bulgaria.

"There's a lot of effort in testing ADCs to treat lung cancer which is still a major cancer worldwide... there's a large number of patients that could benefit from an ADC that proves to be effective in lung cancer and is approved by regulatory authorities," he says. Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, and the leading cause of cancer deaths. There are currently over 20 ADCs from various companies in early-stage clinical trials for lung cancer.

While Peterson and Hurvitz are optimistic for the future of ADC cancer treatments, they are realistic that there could be setbacks along the way. The lead up to the first successful approval of an ADC for breast cancer was a very long and painful one with a lot of false starts, says Hurvitz.

"It's pretty remarkable to see how far we've come in terms of demonstrating that multiple ADCs now are more effective than chemotherapy, and other standard therapies," adds Hurvitz. "I think the hope for the future is moving these agents up into early-stage disease and generating data to show how these agents benefit patients."

This article, funded by Pfizer Inc. and produced by BBC StoryWorks Commercial Productions, is for general information and education and is not intended to be a substitute for advice provided by a doctor or other qualified healthcare professional.

PP-UNP-GBR-10227

Last update

Monday 14 October 2024